How Could It Be?

In the spring of 2021, when I came to really understand that autism being a "spectrum" meant it is different from person to person, it was like a lightbulb lit up in my head.

It may seem as if that should have been obvious, but allow me to explain.

I had a vague picture of the old stereotype in my mind of what autism was before that, and even though I had heard the term "high-functioning autism", I still associated it with some form of intellectual disability.

I was only 7 years old when Asperger's Syndrome was added to the DSM-IV in 1994, so it was hardly something that was widely known and diagnosed during my childhood, or even through most of my teens. I can remember hearing the term Asperger's for the first time when I was 21, but I didn't know what it meant.

At age 34, I found it intriguing to learn that lots of people go undiagnosed through their childhood and adolescent years, only to piece it together it in adulthood. So many, in fact, that some researchers refer to this group as the "lost generation."

By this point it had been nearly a decade since the DSM-V was published, and Asperger's Syndrome and a few other developmental disorders were removed in favor of a single "Autism Spectrum Disorder".

It is no wonder there is widespread confusion about what autism actually is!

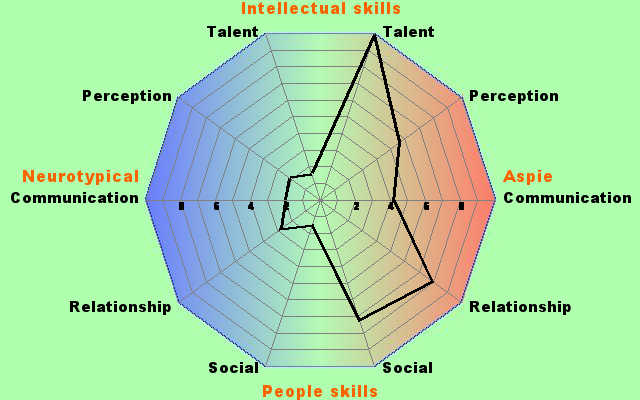

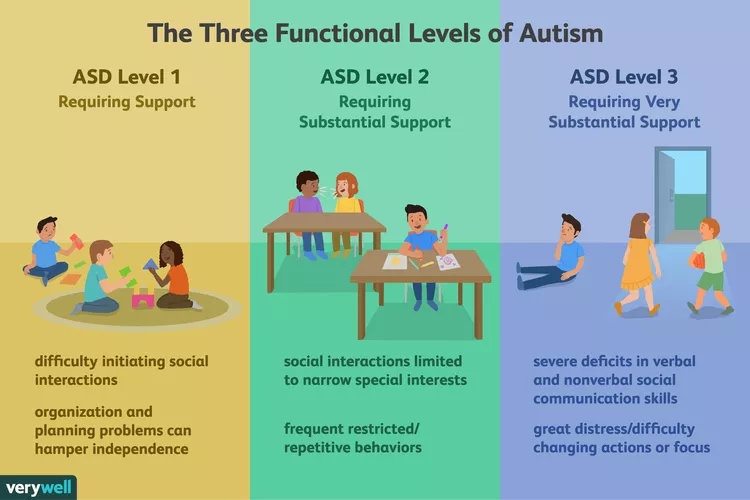

How can two people be labeled with the same condition when one may be be unable to speak and require significant support in their daily life, and another may be socially awkward with above average intelligence and is able to live independently?

To be honest I don't like making that comparison, as it implies that one person is more or less autistic than the other, and that's false. But it does help illustrate the wide range in experience and presentation of autistic traits, which translates to their having varying levels of support needs.

Credit: Verywell / Cindy Chung

Credit: Verywell / Cindy Chung

There are common misconceptions that adults who elude diagnosis in childhood are less autistic, or that "we're all", as in everyone, "a little bit autistic." This is also false.

While there are common traits shared by many autistic people, there is as much variety in autistic people as there is among allistic people.

In SpectrumNews, a publication about the latest news in autism research, neuroscientist Dr. Angie Voyles Ashkam writes:

[Autistic] traits are thought to arise because of alterations in how different parts of the brain form and connect to one another. No research has uncovered a ‘characteristic' brain structure for autism, meaning that no single pattern of changes appears in every autistic person.

Dr. Angie Voyles Ashkam, Brain structure changes in autism, explained

Representation Matters

In April 2021, Josh Thomas, comedian and creator of one of my favorite TV shows, "Please Like Me", publicly disclosed he had been diagnosed with autism. It was a brilliant show that had been close to my heart for several years, with LGBTQ and mental health storylines at the forefront, and without any stigma.

Just a year prior, Hannah Gadsby, a comedian and writer for the show, also publicly shared she had been diagnosed with autism.

Neither of them fit the stereotypical image of autism, and would appear to have achieved an outward level of success by neurotypical standards, at least in their professional lives.

That realization sparked a possibility in my mind. I didn't immediately jump to "maybe I'm autistic, too", but I was intensely curious, especially because I knew much of what the show depicted was based on stories from their real lives.

Please Like Me's finale was 5 years earlier, but at this time, Josh had another show out called "Everything's Gonna Be Okay". He plays an older half-brother and guardian to two teenage sisters after the death of their father, one of which is autistic (and played by an actually autistic actress!).

During the second season, someone suggests to Josh's character that there are signs he could be autistic, too, following a breakup and a pattern of social atypicality. He was in disbelief at first, as there were noticeable differences in him and other autistic characters in the show.

Even his autistic sister dismissed the possibility initially until he described his experience of masking his way through life to hide his natural ways of thinking and being. That part deeply resonated with me, and I know it does with many other late-diagnosed adults as well.

After an online self-assessment suggested he was indeed on the spectrum plus the magic of Hollywood, he was able to jump right into a formal evaluation where he was given a diagnosis.

Just like Please Like Me, this show, at least the part about his own path to diagnosis, was a reflection of his real life.

For me, it was the impetus to start looking in the mirror.

The "A-ha!" Moment

After a few more of these seed-planting moments, I was seeing a pattern and decided to take a closer look at myself.

I have always felt different from others. I was always the shy kid growing up who was obsessed with computers, and although I eventually made some friends in my late teens/early 20's, compared to most of my peers I was still pretty shy.

And that's still the case today, which perhaps makes me stand out even more now as an adult. New situations, particularly unstructured social interactions, are a struggle. I frequently experience situational mutism in groups. My brain is highly analytical and craves logic.

I took a quiz I found online, not knowing if it would say there's no way I could be autistic or quite the opposite.

The results were eye opening. "You exhibit moderate to strong Asperger's condition symptoms," they read, with a recommendation to seek a professional assessment. So that only made me more curious, and I took several more quizzes.

It's not like a BuzzFeed quiz. It's not, like, "What Kind of Shortbread Are You?"

Josh Thomas in Josh Thomas's Comedy Of Self-Diagnosis via New Yorker Magazine.

I figured (and later researched to confirm) that some of the self-report quizzes are more clinically valid than others, but I was amazed at how consistent my results were from one to the next.

On every single quiz I scored above the threshold for a likelihood of ASD. Not once did I score below, nor did I score so high that it seemed unlikely, either.

For the next several weeks, I spent nearly all of my free time educating myself about autism. I was more interested in firsthand accounts of lived experience, wondering if I'd find any of it relatable.

As it turns out, I found much of it to be highly relatable. Almost eerily so.

I ended up reading 5 books in fewer weeks. I spent lots of time on the r/autism and r/aspergers subreddits which exposed me to conversations about autistic life amongst autistic people for the first time. I watched hours and hours of videos on youtube — a mix of firsthand advocates as well as clinicians discussing the diagnosing and presentation of autism in adults.

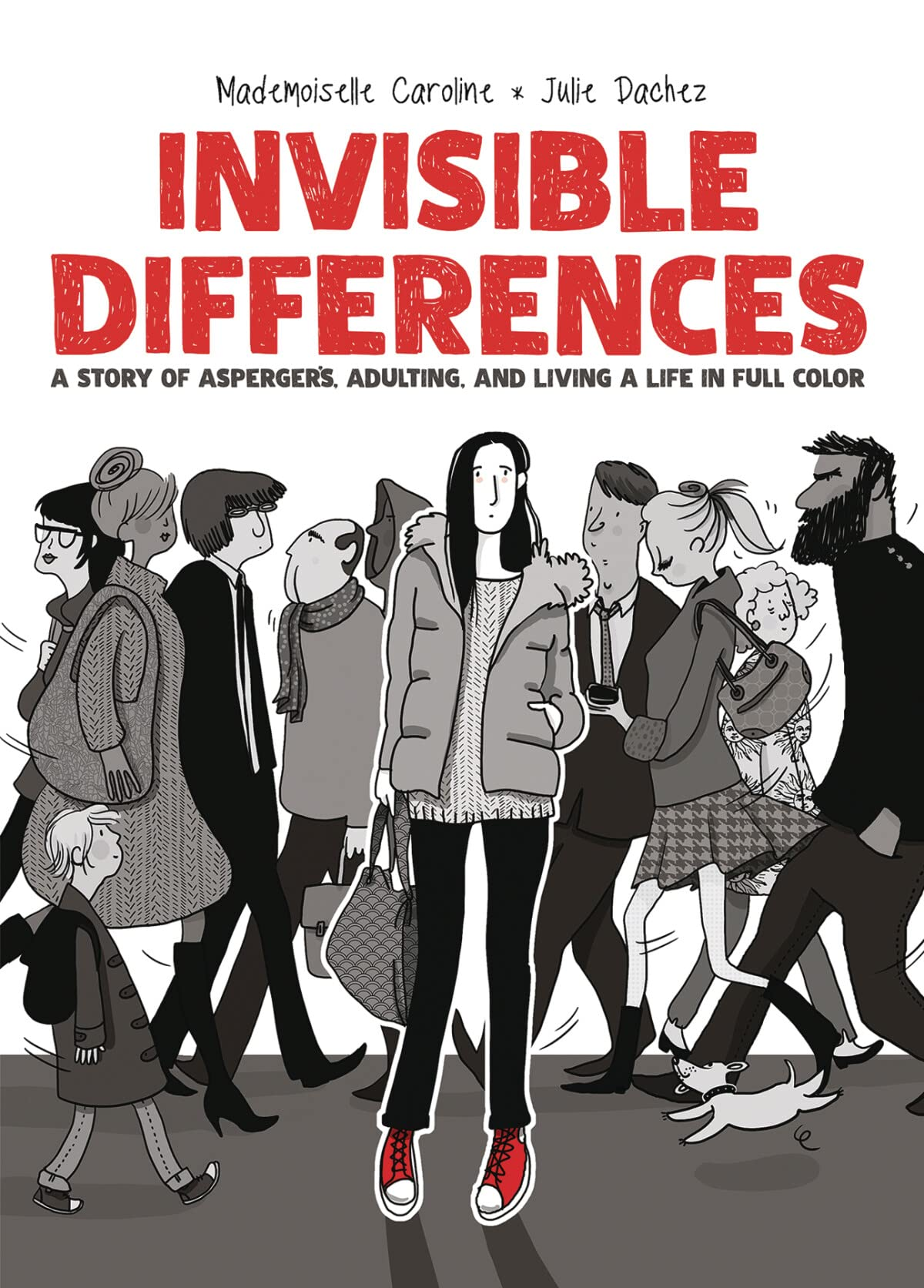

One of my favorite books I read while first learning about autism was a graphic novel called Invisible Differences. It is based on lived experiences of the author, and illustrates daily life of an undiagnosed autistic young adult struggling in her workplace and in her relationship at home before ultimately realizing she is autistic.

One of my favorite books I read while first learning about autism was a graphic novel called Invisible Differences. It is based on lived experiences of the author, and illustrates daily life of an undiagnosed autistic young adult struggling in her workplace and in her relationship at home before ultimately realizing she is autistic.

What made all of that especially interesting to me is in this material, other people were discussing experiences I shared and felt, but had never externalized. How could that be?

When you've struggled to authentically relate to others for your whole life — which happens to be the first criterion for ASD specified in the DSM-V — and you discover a group where you suddenly see your differences and struggles reflected and intuitively understood, it's a profound realization. An "a-ha!" moment.

I was gaining a level of self-understanding that I knew was going to be incredibly important moving forward.

Current estimates put the prevalence of autism at around 1-2% of the global population. The social and sensory differences that make up the autistic experience cut through race, religion, gender, sexuality, nationality, socioeconomic status, and all other ways we as humans group ourselves and form identities around. It truly is an "alien" perspective.

My main interest has always been computers and it takes a lot for me to shift my sustained attention to something else, a concept I later learned to be monotropism.

I can remember thinking there's no way I would have spent as much time with such intense interest as I had researching if it wasn't because I was learning something as important as how to describe my inner world for the first time.

Autism is described by others through observed external behavior, but its neurological basis makes it primarily an internal experience.

The next step was to tell my closest friends what was on my mind. I was curious if those who knew me best would see what I saw. Admittedly I was a bit nervous, but each of those conversations (there were 3 of them) were remarkably anticlimactic.

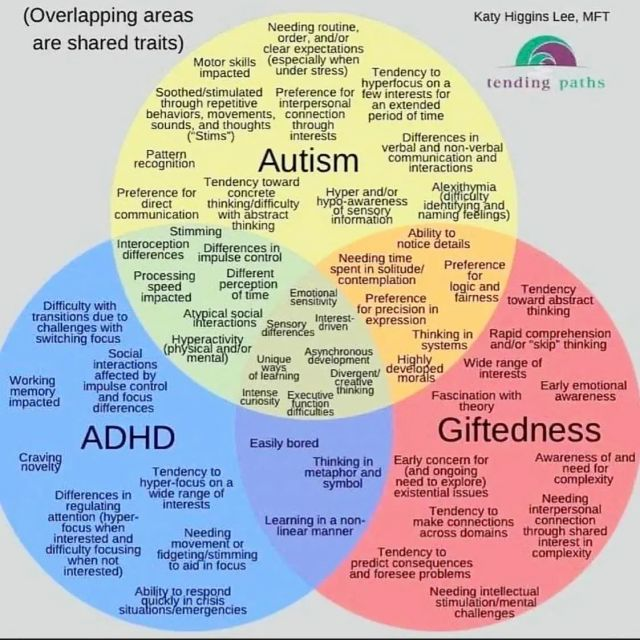

"I think I'm autistic," I blurted out, to which they each replied "yeah, that makes sense" without needing to be convinced. Two of them are diagnosed with ADHD, which I was learning is also considered a type of neurodivergence that shares some overlap with autism.

I know it's anecdotal, but I don't think it's just a coincidence that my closest friends are also neurodivergent.

Both of my younger brothers are also diagnosed with ADHD, so the family history of neurodivergence was yet another signal.

Credit: Katy Higgins Lee, MFT

Credit: Katy Higgins Lee, MFT

How To Move Forward?

By that point I was nearly convinced, and I started giving serious consideration to finding a professional who could conduct a formal assessment in order to confirm my suspicions and make sure I wasn't overlooking other possible explanations for my autistic traits.

One of the friends I had confided in is a mental health professional, and we had several helpful discussions during which he explained how the diagnosis process works including what other possible conditions would first need to be ruled out, how to navigate health insurance issues, and what my options were for finding a provider that could assess me.

Through my research process I had become acquainted with the DSM-V and the diagnostic criteria for ASD. The pattern of autism was obvious to me, and my brain is great at spotting patterns and details that others miss — a common autistic strength. Looking back through my life history, it seemed to me this pattern was most likely significant and persistent enough to qualify for a diagnosis.

See, when you're adult and questioning if autism is an accurate description of how you experience being in the world, it triggers the reprocessing of old memories of awkward encounters, uncomfortable feelings, misunderstandings, social/relationship failures, as well as unique interests and strengths.

In each situation, you find yourself asking, "could being an undiagnosed autistic person explain this?". (Even now, more than a year post-diagnosis, this happens to me quite regularly.)

But after everything I had learned, the idea of going through the formal process was daunting.

For starters, I knew it would probably be expensive. I wasn't sure if insurance would cover it or not. More concerning was the fact that in New York City, where I live, it's more common than not for mental health professionals not to accept insurance anyway. Regular therapy sessions can set you back a couple hundred dollars per hour.

The act of searching for a psychologist or psychiatrist meant making phone calls to strangers, without a referral, and assuming I'd run into pushback. I'd read way too many accounts of bad experiences others in my position had been through.

Adults are still too commonly dismissed when they suggest the possibility of having ASD simply because they don't fit the old stereotype of autism, and many practitioners still only work with autistic children. (Although thankfully this is beginning to change.)

Sadly, if you are capable of making eye contact, don't sound like a robot when you speak, have a job, or have developed coping strategies that allow you to mask your autistic traits too well, this is a possible (though certainly not inevitable) reality you must be prepared to encounter. It can be a huge setback, both financially and emotionally.

In a 2017 study of the barriers to formal diagnosis adults face, Dr. Laura Foran Lewis found:

Fear of not being believed by professionals was identified as the most frequently occurring and most severe barrier. Professionals must strategize to build trust with individuals with ASD, particularly when examining the accuracy of self-diagnosis.

Dr. Laura Foran Lewis in A Mixed Methods Study of Barriers to Formal Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder in Adults

I prepared a script to follow and worked up the courage to call a few local psychologists and psychiatrists I found in my health insurance's directory of care providers. Each turned out to be a dead end, despite their profiles in the directory listing autism or neuropsychology as a point of expertise.

I contacted a neuropsychology testing facility that specialized in autism assessments, but unfortunately the minimum, up-front cost started at $5,600 with no insurance accepted — well beyond what I could afford and felt was reasonable.

The challenge of figuring out how to get a formal diagnosis was becoming overwhelming, and I decided to take a break for a bit.

Although I still planned to follow through when I could, I didn't feel a need to wait for a professional to validate what I already knew to start making some changes.

Real-time Struggles

One of the more immediate contributing factors to suspecting I was autistic was my feeling totally incompatible with my job as a sales engineer for an advertising technology company. I had extensive experience on the technical side of the digital advertising industry which is how I got the job, but to my dismay this company placed heavy emphasis on the sales part of the role and not so much on the engineering.

What I found hard was the social and relationship-building aspects of the job, the unpredictability of my schedule, and the lack of clear details in advance of meetings with potential clients — all things that were not just easy and non-issues for my colleagues, but also enjoyable.

Yet when it came to the company's product, I absorbed the documentation and developed thorough knowledge of how it worked in a short period of time, which my boss and other executives found amazing.

This was the first job I'd ever held that required more soft skills than the hard skills I was used to getting by on, as those overlap with my special interest. If I had known I was autistic back when the recruiter initially reached out, I wouldn't have given it any consideration.

My manager, who had made positive comments about my curiosity and how my brain worked differently, asked "why do you need so much information before meetings?"

I was confused and assumed everyone would benefit from being better prepared, but lacked the self-knowledge or language to describe the daily distress I felt without it. That question left me stumped over why I needed something others shunned, and feeling misunderstood on a fundamental level.

It's really ironic that at the time, something I saw as a big issue was that the sales team frequently didn't include me on enough of their calls (perhaps another sign by itself...), which I felt was interfering with my ability to do my job considering my primary responsibility was to support their efforts from a technical perspective.

It wasn't that I wanted more meetings because I enjoyed them — quite the opposite. I found them so uncomfortable that I thought the only thing that might provide some relief was more practice. I was desperately craving a more predictable, routine experience.

I was the first person to have my role in the company and I attributed the sales team's disinterest in cooperating with me as a process matter that would take time work itself out. I am glad it never did, because I was already feeling burnt out despite not having more than 2 or 3 hours of meetings in total on a typical day, and with little else to do. Even that was exhausting to the point that outside of work I needed lots of time alone to recharge.

I was used more for giving product demos and did a decent job at that as it was mostly just following a script, and I knew the details of how the product worked better than any of the sellers.

Still, no matter how many demos I gave, I was nervous every single time and would spend at least an hour rehearsing before every call. There were a couple of times I was given "constructive" feedback that I could be overwhelming and didn't need to go into so much detail during demos…I was basically infodumping.

Suffice to say, being undiagnosed can be very confusing. I found the "hard" parts of my job easy, and the "easy" parts hard.

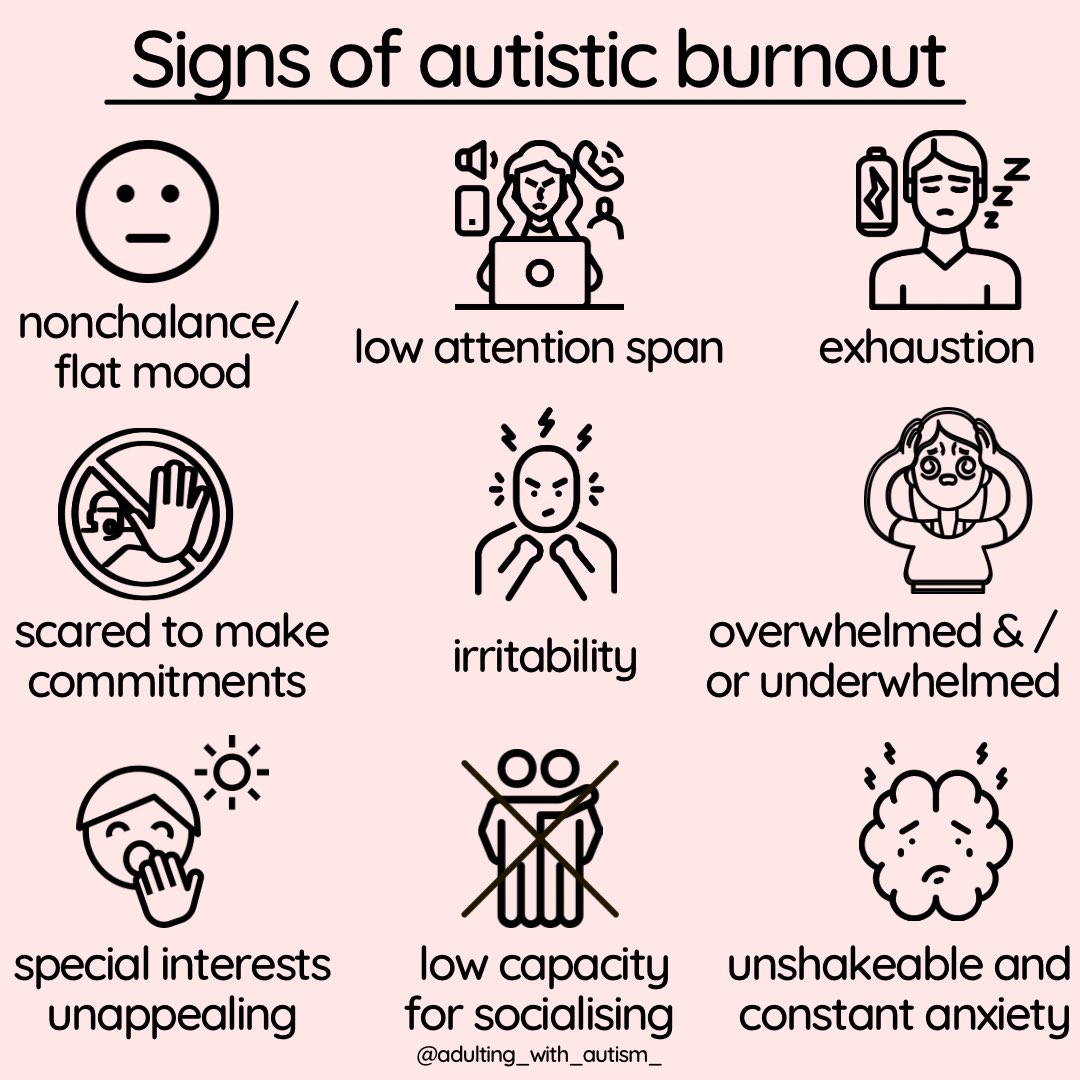

Credit: @adulting_with_autism_ / @autistic_callum_

Credit: @adulting_with_autism_ / @autistic_callum_

Once I realized that my strengths and weaknesses pointed at autism, I knew a job shift back to something that was more closely aligned with my special interest was crucial for my well-being. It wasn't the kind of situation where reasonable accommodations could have been made, it was just not a match for me.

I Found A Psychologist!

In September, about 4 months after my initial discovery, I started a new job as a software engineer. Programming, and particularly web development, has been a passion since I was in 6th grade. Although my combined experience in programming and the advertising business had lead me to other other jobs beyond just coding full-time, that is what I've always always enjoyed the most.

Even though it was very much a welcome one, I decided I'd give myself a couple of months to adjust to the transition before resuming my efforts to seek a formal diagnosis. I wanted to feel some much needed stability before voluntarily adding more stress to the mix.

I also looked at this time as an experiment of sorts. Part of me wondered if I just tried to focus on my daily life and pushed getting diagnosed to the back-burner, would the desire to follow through go away? Would my mind change about my being autistic?

No, it didn't at all.

Things were going great for the first 2 months of the new job. I was really enjoying the work. I got to spend the majority of my day working with code and had a predictable schedule with minimal meetings. My responsibilities were more aligned with my natural strengths in attention to detail, noticing patterns, ability to hyperfocus, and thinking in systems.

It was around the end of October that I encountered some unexpected changes at work that were disorienting and destabilizing. I felt I was heading for a burnout, and that it was important to reprioritize finding a psychologist to help make sense of what I was going through, and everything I had learned about myself in the context of autism.

I wanted to be able to talk to my manger about what I found challenging and advocate for my needs, but I wasn't comfortable explaining the what and the why behind that without getting diagnosed first.

Another search of my insurance provider's directory turned up a new tele-health service for mental health called Alma. I was skeptical at first and had a preference for in-person care. Knowing how difficult it is to find someone willing to assess an adult lead me to believe that not being able to be in the same physical space would only add to that.

But as the US was in the midst of another COVID-19 surge, most providers were only seeing patients virtually at that time.

Alma had the benefit of being covered by insurance, so I was only responsible for the copay. I figured even if it didn't ultimately lead to a diagnosis, it could still result in a referral and validation that I was on the right track.

I also liked that with Alma, rather than cold calling a provider, the process started with a 20-30 minute questionnaire about what you're seeking help with, your current state of health, etc, so that they can match you with a shortlist of compatible therapists.

I was provided 3 choices of psychologists experienced in working with autistic patients, along with background information I could use to make an informed selection — an ideal process for an autistic person. Once I made my selection, my information was sent to the provider so they, too, could validate they could provide the help I was seeking.

Soon after, we then had a brief consultation call where I reiterated I was seeking confirmation for whether or not I was autistic. I had done months of research, taken several screeners, compiled a list of traits and experiences going back to childhood that was organized by which category of diagnostic criteria they fell into, and was even able to explain why I didn't think some other conditions like general anxiety or depression weren't better explanations for the patterns of thought, behavior, strengths, and weaknesses I saw in myself.

I wanted to make it clear that autism wasn't a conclusion I had jumped to, and what I was looking for from a healthcare provider was someone who would take their time to conduct a holistic look at me before reaching an opinion of their own.

Diagnosing autism is still not an exact science. No single diagnostic method or tool is universally endorsed among clinicians. Ruling autism in or out because of a single test score or a single invalid stereotype such as eye contact is, in my opinion, not in the best interest of the person being evaluated.

I appreciated that in that initial consultation, my psychologist expressed an appropriate amount of skepticism balanced with an open mind that perhaps I might really be autistic, and that she agreed it was worth exploring.

Assessment Time

Together we decided that the right next steps, besides me sending over all the information I had compiled, was to schedule weekly clinical interviews for the next several weeks.

I was both nervous and relieved. Nervous because despite moving forward by choice, it meant opening up in depth about my life history to a total stranger while seeking help, with the fear that I'd soon be shown how my mind had somehow tricked itself into thinking I'm actually autistic. This too would be exhausting, but there was relief in the fact that I was moving towards a confirmation. I knew I wouldn't have been moving forward if I had more than surface level doubt.

Our sessions lasted an hour each, and we discussed a range of topics including my relationships with family, friends and romantic partners, my work history, how I handle novel social interactions, my experiences in school as a child, teen, and in college, how I spend my free time, and more, all in great detail.

We also spent time talking about my strengths, such as how I'd been able to turn my lifelong interest in computers into a career despite not completing a college degree.

A couple years back I had taken a strengths assessment by Gallup for the job I had at the time which identified the top 5 themes of my strengths as: deliberative, analytical, futuristic, intellection, and strategic.

Although the DSM only recognizes what it calls "deficits" in the diagnostic criteria, most of those strengths rely on traits such as the ability to hyperfocus, attention to detail, good memory, and creative thinking that are common for autistic people with an Asperger's profile.

At the end of each session she'd give me homework to complete before the next one. These included some theory of mind assessments such as watching videos and explaining my understanding of what was going on based on the subjects' interactions, taking more assessments such as the Empathy Quotient, Systemizing Quotient, and Camouflaging Autistic Traits Questionnaire, finding pictures from my childhood and teen years, and describing in depth what I thought masking was along with examples of the camouflaging strategies I use to appear "normal".

I didn't know how long this process would take but was happy I was being taken seriously. Then, at the end of the 4th interview, she said she agreed a diagnosis of ASD was appropriate.

I felt a range of emotions from relief to even guilt, like I had somehow cheated because my path to that moment wasn't as arduous as it unfortunately is for many others. I knew how lucky I was to find a psychologist who was just as interested in my inner experience as the external traits she could observe, and how autism is more than a collection of deficits.

Now, with that settled, I could shift from questioning to acceptance with confidence.

It would still take time to fight off feelings of imposter syndrome and to learn how to advocate for myself as an autistic person, but getting diagnosed not only provided answers to questions from my past, it also provided valuable insight for how to navigate relationships, work, self-care, and adulting in general moving forward.

Although all autistic people are different with their own set of traits and experiences, from all other accounts I've read and watched, that theme is nearly universal among late-identified adults.

We now have an understanding of the framework that underpins our existence: we have come to accept our strengths and know that they are not diminished by our challenges; we now know how to exercise better self-care and are healthier and happier for it; we no longer waste energy trying to be successful neurotypicals and, instead, focus our efforts on thriving as our autistic selves.

Erin Bulluss, Ph.D., and Abby Sesterka in When a Late Diagnosis of Autism Is Life-Changing

Ultimately, that is what getting diagnosed as an adult is all about.

References + Resources

-

Identifying the lost generation of adults with autism spectrum conditions

-

Autism Spectrum Diagnosis Helped Comic Hannah Gadsby 'Be Kinder' To Herself

-

Invisibile Differences: A Story Of Asperger's, Adulting, And Living A Life In Full Color

-

A Mixed Methods Study of Barriers to Formal Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder in Adults